Music in Theology

What is

Music? Sound which unites our being at every level by uniting both halves of our brain at a deep level.

Physically it is nothing more than vibrations of the air, and yet it has the ability to move us onto a different and

higher plane of existence because of the effect of these vibrations on our physical, emotional, spiritual and

psychological existences. Our bodies respond to physical vibrations even as our minds interpret the result in a

different way. Take, for example, the speed or beat of the music. If this is lower than our heart rate of 70 beats

per minute, then we feel more relaxed because our heart rate attempts to reduce to match the beat of the music. If

it exceeds that number then we feel more energised as our heart tries to match that of the music. Equally if we know

that music can move, inspire, depress or even make us laugh, and psychologically we prefer consonant harmonious

music rather than a series of discords.

Indeed we can go further, even if music

seemed to play but a minor part in the ministry of Jesus. "And they went out and sung an hymn"

(Matthew 26:30). Jesus obviously sung and therefore had some regard for music. How much we do not know. He was much

more concerned with a ministry of healing and teaching. Jesus, faced with the legalistic teaching of the Pharisees

in which man was made for the sabbath and not the other way round, restored the balance by holistically summarising

the Law, i.e. all the instructions in the first 5 books of the Hebrew Bible, into 'Love God, love your fellow human

being'.

Now this is important because, in essence, here we are dealing with the

inbuilt rhythms of the universe. His healing and teaching was nothing more than tapping into the

structure of the universe at its elemental level, one of vibrations, and appealing to the right hemisphere. Illness,

for example, is when we are out of tune with ourselves. The whole universe is nothing more than a series of

vibrations obeying the various laws which gave them utterance. Everything vibrates, whether colour, light, or those

denser forms which gives us solid structures. Relationships in other words, when 'harmonious', breed wellness.

Music fits into this category in that it is nothing less than a series of vibrations,

and as such observes this core principle of the universe. On a personal level we can go further. Singing

has long been recognised as one of the most fulfilling activities in which humanity can engage, especially when

undertaken with others. This operates in 2 ways. First, when you sing, you vibrate various parts of the body, from

the head, down the spine, into the abdomen, finally into the legs. Not for nothing do Buddhists chant 'om' (in

reality 'ahoommm'), which if you try it has a remarkable effect on resonating sequentially the whole body.

Second, when singing in choirs, there is a developed sense of not only harmonious

belonging, but also of producing something greater than the parts. This is particularly so when

performing religious music, particularly, in the West, of the Renaissance and Baroque period with its accent on the

interplay of equal voices (i.e. not melody and accompaniment). With the rise of melody and harmony the idea of

master and servant, dominant and dependent, came to the fore, an imbalance among humanity and therefore an imbalance

in Nature. We may love the beauty of the melody. We forget the harmony. It is the equal interplay of voices

particularly of the Renaissance and Baroque period which is so significant, this feeling of equal importance and

respect, this democracy of being. It is the resonance of this interplay which is most in touch with the natural

order of the Universe by taking the sounds which arise from Nature (the human voice, the sounds made out of

materials constructed out of Nature's store) and playing them back to Nature. Nature gives and then receives.

Humanity receives and then gives. The result is a feeling of oneness, an inter-connectivity, not only with each

other but with something outside the musicians. This is hard to define unless it has been experienced. People who

have often describe it as an awareness of having created something greater than merely the sum of the parts, in

which the feeling of self is somehow lost.

Science entered the fray in 6th century

BCE Greece with Pythagoras who employed mathematics in determining the properties of sound. He is

credited with developing the idea of 'perfect' intervals, i.e. those which sound the most harmonious to the human

ear. Using only perfect numbers he identified the unison (mathematical ratio 1:1), the octave (ratio 2:1), the

perfect fifth (ratio 3:2) and the perfect fourth (ratio 3:4). Even to this day we regard these intervals as the only

perfect ones because to our ears they feel the most consonant and harmonious. Indeed we can go further.

We can see an even greater and more universal beneficial impact of this science of sound by

looking at how these terms affect our every day lives. Harmony (from the Greek meaning literally fitting

together, agreement or concord) has struck such a 'chord' in human life that we now use it to describe

relationships, colours, living together, living with nature, and is often used in conjunction with beauty,

orderliness, peace and wisdom.

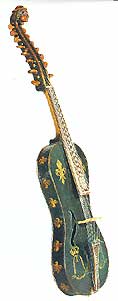

An interesting question is what is the effect of the

kind of music on the listener. To my mind there is nothing to match the purity of the unaccompanied human

voice in counterpoint to enter some form of spiritual realm. This is as direct as music can be - there are no third

parties, like instruments, involved where one can convey the music only through a constructed medium with all the

problems that entails. A hidden one is that of tuning. With the exception of the violin all instruments have a

specific pitch for a given note. Western music is based on a 12 note scale, octave to octave. Everything is

compromise because while it is possible to create a relatively 'perfect' Pythagorean scale on one note, say C, when

you try to play the resulting scale which starts on D, the intervals are well out. The solution is to compromise the

tuning of every note so that all scales are equally out. Thus various standards or differences of tuning methods

have been, and still are especially in Baroque music, employed. It usually means slightly flattening the fifth and

sharpening the third. Even on the piano the octaves are not perfectly tuned. The human ear prefers to slightly

sharpened octaves going up the keyboard (otherwise they sound dull and somehow wrong, and flattened going down for

the same reason. Only the human voice can make every key sound perfectly in tune.

Another

interesting effect of the variety of music is the so called 'Mozart effect' on the ability to learn. Some

studies indicate that pupils have enhanced their learning abilities while listening to harmonious Mozart music at a

speed around that of the human heart (ca. 60-70 beats a minute. Other studies have not been able to replicate this.

One famous study took some mice and timed their ability to solve a maze to reach food. They then divided the group

in 2. One group listened to Mozart for 24 hours (!), while the other group listened to Heavy Metal. When placed back

in the maze the Mozart group solved it quicker than before. The Heavy Metal group, however, caused the experiment to

be stopped when, instead of solving the maze, they attacked and killed each other. Numerous cities have also

experimented with playing Mozart type music in crime spots late at night. Most reported some success (one London

underground experiment caused a 22% drop in crime) though it could not be established whether this was the result of

the music or that criminals so hated what they heard that they left the area to commit crime elsewhere.

What all this does indicate, I feel, is that we are profoundly affected by what we hear. This

is no less so for religious or mystical music as for other forms. As with watching violent movies we are

subconsciously affected by everything we hear. We must be. Why else do we sometimes rant or rave, or utter sweet

nothings? Why do we feel enervated by some music, relaxed by others. I am indebted to J W Slaughter who in the

International Journal of Ethics wrestled with the problem of what constitutes religious music. Only a small part of

life is governed by abstract intellectual thinking. Most of our experiences have a personal flavour, that estimate

of value which is the mark of an emotional attitude. What is mysticism. For him it starts with the emotions but then

goes further. "It is the intuitive judgement in which no attempt is made to clarify the terms. It is not a pure

feeling state, but feeling attitude, or feeling comprehension." Mysticism, yes, embraces feeling but then

proceeds one step further in which "the state of mind becomes a source of satisfaction, and therefore an object

of realisation in itself". Thus the poet or ordinary composer is always conscious that his vision lies within

the limits of his imagination (e.g. earthly based images and feelings). The religious based composer seeks outside

of himself and his environment to thoughts of eternity and the supernatural, and in so doing carries us with him.

Which is why, for example, Bach succeeds while many a modern worship song fails. It is caught up too much with

creating a feel good factor, with promoting the image of the composer or performer.

One final conundrum. We hate perfection in music. By that I mean strict tempo.

Everything has to be elastic. Digital music, i.e. that produced by synthesizers to a strict tempo, never seem to

involve us. We long for the pulling back of the music before a climax, the broadening out of some themes or

accelerating others. 'Rubato' it is called. It seems to fulfil not only our emotional needs, but that of perfection

of understanding. I wonder why!